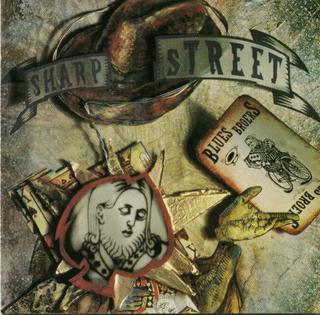

THE BLUES BROERS

SHARP STREET (Guava Records 1995)

From The Blues Broers website:

SHARP STREET (GR003)

Cooking instructions: Just take one Sharp Street CD and add Hi-fi. In 1995 the Blues Broers risked ending up like so many local bands; seen but not heard, so they made the sound decision to go digital.

In an eclectic mix of musical ingredients they motor through Soul City in ‘Automobile,’ frolic with the jazz of ‘Blue Dolphin’ and boogie down to new depths of depravity in ‘Submarine.’ With the spine-chilling guitar playing of Albert Frost and a Hammond organ so loud your neighbours will call the Police, Sharp Street is a recording to satisfy most appetites. Even though it's been on the shelves for a few years it still tastes as fresh as the day it was mixed. Try some today. You can download selected excerpts.

"Definitely worth a place in any blues collection."

Phil Wright - Music Source Magazine, November 1995

"I was hooked . . . and remain so."

Richard Haslop - Scope magazine, September 1995

"Sharp Street is a must for every Blues Broer and sister."

Coenie de Villiers - De Kat Magazine, January 1996

"Some fine playing here"

Bruce Iglauer - Alligator Records Chicago (letter), December 1995

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Blues Broers was one of the offshoots (in a manner of speaking) of The Flaming Firestones, the band that was the forerunner of the early Nineties blues boom in Cape Town. The founder members of The Blues Broers were Rob Nagel (bassist and blues harpist and occasional saxophone player in All Night Radio and the blues harp player and occasional vocalist and guitar player in the Flaming Firestones) on bass guitar and blues harp, Frank Frost, a veteran of the Cape rock scene (amongst others Black Frost) on drums, John Frick (brother of Clayton Frick, guitarist vocalist of the Flaming Firestones with whom Johnny played in its last days) on guitar and vocals and Simon “Agent “Orange who plays keyboards and also sings a couple of songs.

The Blues Broers was probably the best of the new crop of so called blues bands who popped up after the demise of the Flaming Firestones and who were motivated by the founding of The Smokehouse blues club. Most of these bands appeared to operate under the misguided assumption that blues was originated by Stevie Ray Vaughan and ZZ Top and on the face of it they showed almost no inclination to investigate any earlier form of blues, apparently so ignorant of blues history as to refer to their versions of Vaughan’s version of the Howlin’ Wolf tune “Commit A Crime” as “a song by Stevie Ray Vaughan.” These musicians were essentially hacks who believed in the necessity of endless guitar solos in every song, and to my mind they were simply rockers who were happy to turn to “blues” because at the time the Smokehouse was about the only Cape town venue to book bands but would allow in only blues bands. The definition was never all that purist and by and by it was more or less simply a rock venue although biased towards blues rock.

Although they also had the Z Z Top and Stevie Ray Vaughan roots (and tunes) The Blues Broers did their best to be a proper blues band that swung like the best off the Chicago bands of the Fifties and in this aspiration they were greatly assisted by the two factors that made them unique amongst their peers: firstly Rob Nagel’s blues harp virtuosity and secondly Agent Orange’s keyboards. The other blues bands (except for Clayton Frick’s band that featured a harp player from the punk rockabilly band the Mavericks) were built around guitarists with Stevie Ray Vaughan fixations. The two elements of blues harp and keyboards plus the general tasteful and non-grandstanding playing of successive guitarists contributed to a sound that made The Broers almost sound like an authentic house rocking ensemble from the Southside of Chicago. There was also a brief period when they had a horn section and even backing singers, the Soul Sisters, to emphasise the “authenticity divide” between The Blues Broers and their peers.

The Broers have been going for about eleven years now, a kind of a record for a Cape Town band, although there have been regular personnel changes, mostly on the guitar side, like a South African version of John Mayall’s various groups. Johnny Frick was the first to go and was replaced by the late great Nico Burger on guitar only and John Mostert as vocalist. I saw the first gig of the newly reconstituted Broers at the Kimberley Hotel in Roeland Street where they were also attempting to re-establish a blues club, the Smokehouse having gone belly up sometime before when Clayton Frick, the driving force behind the club, left South Africa. Nico’s playing was a bit uncertain but was. as always, still a pleasure to hear. It quickly became clear though that Mostert was not much of a vocalist; he certainly did not have the pipes or the authority to be much of a blues singer, and he did not have much stage presence either. As it happened, Nico’s tenure as Blues Broers guitarist was short-lived. I believe he was kicked out of the band because of drinking problems (which ultimately led to his death not too long afterwards), to be replaced by Albert Frost, Frank Frost’s then teenage son. John Mostert remained with the band until fairly recently when he too left (or was asked to leave) and now fronts the Boulevard Blues band. In the meantime Frank Frost has also died.

Albert Frost was still at school when he started playing with the Broers as second guitarist behind Nico Burger but he has now matured into a great player in the Burger tradition (if one may call it that) where sensitivity, subtlety and taste are more important than guitar histrionics. He has backed Koos Kombuis (the Blou Kombuis live album), plays with Agent Orange in a band called Frosted Orange, has played guitar on a number of sessions and also goes out on his own.

Sharp Street was released in 1995 and was the first CD on the band’s own imprint, Guava Records, coming after two cassette tape only albums Shake Like That and Damn Fine Mojo. The Blues Broers have since released two more CD’s, Been Around and The Cellar Tapes, the latter consisting of live recordings from the Hidden Cellar venue in Stellenbosch.

Commendably the songs on Sharp Street (named for Willem Moller’s Johannesburg studios where the songs were recorded) were written by either Rob Nagel or Agent Orange; with three songs written by partnerships within the band. It seems that the mission was to record a blues album with as much authenticity as possible and without the trappings of rock influence and they have succeeded in this endeavour. Unfortunately the result is that one’s overall impression of the album is that it lacks spark; it is just too damn tame. It is possibly the politest blues album I have ever heard and is certainly for the most part no more than workmanlike “white blues.”

It is only from about the fourth track in that the band starts to kick a little ass and that one’s interest is aroused. All through the album one invariably longs for the guitar to let rip, for Agent Orange to really pound the keyboard with a two fisted punch or for one of the vocalists, but especially John Mostert, to break loose with a real blues roar. Possibly Willem Moller, producer and engineer, must shoulder some of the responsibility for not being able to produce a more lively outing and for quite often inexplicable mixes that blunts Frost’s or Orange’s contributions.

Neither John Mostert nor Agent Orange, the two main vocalists, have strong voices but Orange at least tries to inject a certain sly ribaldry into his renditions of his own songs, but neither he nor Mostert have the necessary blues colouring in their voices that is so vital to invest the material with authority. Mostert in particular represents a very firm “no” answer to the perennial question “Can The White Boys Sing The Blues?” His voice is so bland that one doubts whether he has ever had the blues. There is nothing distinctive, or even just quirky, about his timbre or phrasing nor is there any power or passion. If ever I’ve heard any singer “going through the motions,” then it is John Mostert.

The instrumentalists perform virtual academic blues, a pastiche of the blues, and as a result the tracks that grab one’s attention stand out mostly by comparison with the weaker material. Albert Frost is a fine guitarist and can be counted on to play without bombast and it is good that he doesn’t rely on second hand Stevie Ray Vaughan mannerisms but even so, after a while one yearns to hear a bit more of the fire and passion that blues playing should show.

The album opens with something of a Rob Nagel hat trick composition-wise in that he wrote all three opening tracks. The first number is “My Automobile” which is yet another car’n’sex song with obvious Z Z Top roots but where the Texas boys would have made the song sound like a Ford Mustang, the Broers’ instrumental reticence and particularly John Mostert’s almost disinterested vocal makes it sound like a 1965 model two door Ford Cortina. “My Automobile” could have been a killer opening cut if the band had put a bit of muscle into their playing and if Nagel had sung his own song (in fact he should have sung all his own songs on this album.) As it is, Sharp Street’s opening salvo consists of three of the weakest blues I’ve heard in a long while and does nothing to inspire confidence in the future conduct of matters. The first cut on an album should grab you by the scruff of the neck and destroy all resistance. In this case “My Automobile” is actually so pathetic one wonders why white people are content to play the blues with such mediocrity. And the experience doesn’t get much better for two more tracks.

“Graveyard Train” follows. The immediate improvement is that it is a vehicle for Rob Nagel’s blueswailin’ mouth harp with no Mostert vocals in sight. Unfortunately for a song with such a title it is a rather soporific performance all round and sounds less a nightmare trip than a low-key senior citizens’ excursion to Forest Lawn. The rhythm section could have done well to pound out a strong, tight approximation of a train rhythm (and it is instructive to compare the Creedence Clearwater Revival “Graveyard Train,” definitely no relation, to The Blues Broers track) and a more fiery guitar solo would also have improved the performance. Rob Nagel does a nice virtuoso thing and manages to equalise, he just can’t net the game saving goal. I began to wonder why I was bothering to listen to this stuff when I had so many Muddy Waters CD’s I could enjoy.

Third track in is “Dolly Mae” (not exactly the name one would associate with a blues man’s cheatin’ woman; sounds more like a Hillbilly girl) with yet another lacklustre John Mostert vocal and though he bemoans being cheated and lied to by the eponymous femme fatale he does not convince the listener that he is at all stressed out by her shenanigans. As I’ve said before, one gets the impression that Mostert has never had the blues. He is really going through the motions here, admittedly with possibly the weakest lyric on the album, but one desperately wishes for some semblance of emotional connection with the unhappy situation he is singing about. The only saving grace of the performance is Albert Frost’s at times quite vicious guitar playing; he sounds as if he is really the one who is pissed off at the woman and is intent on making up for Mostert’s indolence. And that is the sadness: it would have been a good little number had the vocals been any better.

So, just as I am getting really fed up with the blues-by-numbers I’m being subjected to, up pops Agent Orange’s first tune, “No-one’s Going To Take Me Lying Down,” and my interest is rekindled. It is a good lyric, a sardonic reflection on the life he’s escaping, sung with enthusiasm and with energetic backing (although the slide guitar filigrees could have been more sharply defined.) It sounds so much better than “Dolly Mae” almost simply because John Mostert is nowhere near it, but not only for that reason. Agent Orange sings his own lyrics with conviction and maybe this is why, weak voice apart, Mostert falls short: he cannot bring true conviction to Rob Nagel’s lyrics. Plenty of “traditional” blues have pretty trite and clichéd lyrics, if one gets right down to it, but they are redeemed by the performance of the blues man or woman who at least sound as if they sing, and play, from the depths of a very real, ancient deprivation. They have the blues, whether genuinely or by transmitted convention, and they can communicate this feeling to their audience. This is also the difference between Mostert and Orange: the first simply narrates the words of someone else’s song but brings nothing more to the party, certainly not commitment; the latter sounds as if he believes in the song and thereby persuades the listener to believe in it also.

Next up Rob Nagel deals “I’m A Wildcard,” a Z Z Top homage/parody/rip-off, his sole vocal turn on this album. It is jolly good fun though and the second of a three song combination punch in the centre of the album, being followed by “Glove,” another Agent Orange number with the most authentic Hubert Sumlin style rave up of a Chicago blues riff on the album and arguably its highlight with the winning combination of strong playing, good lyrics and exuberant vocals. This song deserves to be a South African blues classic.

After the visceral excitement of “Glove,” the boys in the band decide to show us their serious side and their serious chops with the smooth, jazzy instrumental “Blue Dolphin,” possibly a subtle homage to The Green Dolphin restaurant and live jazz venue in Cape Town’s V & A Waterfront. Pleasant but inconsequential music for a retro cocktail lounge.

“Electric Train” comes rolling up next and is just about the most cabaret-like number on the album with Agent Orange’s semi-humorous observations on characters seen on the train. In concert the performance featured strong stomping boogie woogie playing by Orange but this is sadly lacking here and would have greatly improved what is otherwise a lightweight number, filler actually, that is saved by Orange’s vocals. The idea of this slight tune being left to John Mostert is almost too ghastly to contemplate.

After a long and happy absence Mostert makes a reappearance on Rob Nagel’s “Nothing On The Blues,” a would-be blues standard. Alas not on the strength of Mostert’s version of it. It is a true regret that he was given the opportunity to muzzle to death with his gums this potential show-stopper of a song. This man should have never been in any self-respecting, aspiring blues band. Mostert also subjects the third last and penultimate songs on the album (“Can’t Come In The Door” and “Hell No,” Rob Nagel songs, all) to the same death by wet blanket. It is incomprehensible why he was even allowed into the studio unless he had contractual entitlements. Nagel should have sung his own songs; he couldn’t have done a worse job.

Fourth last track is the Agent Orange fantasy “Submarine,” (patently not a yellow one), a lascivious little naval ditty in the well-known blues double entendre tradition with mention of periscopes going up and “torpedoes” and so on. It is another fine jumping blues but lyrically, though fun, is a little too close to a jolly Music Hall knees-up for comfort.

Agent Orange is also responsible for the closing number “Magic Alice” which is not strictly a blues but rather a whimsical, psychedelic pop-rocker in the late Sixties English tradition complete with wah-wah guitar and a backwards voice at the end. It is an entertaining, macabre little song about a girl who strangles her mother with a rosary and it appears that the tale is narrated by the Big D (or the Big S) himself, calling his cute little demon home. Not a very strong closer but definitely a fun little number.

So, all in all, a curate’s egg of an album with highlights that stand out precisely because they languish amidst dross. In a perfect world Sharp Street will be re-issued with John Mostert’s vocals wiped and replaced by a decent singer. As it stands, the album does not deserve to be a classic example of mid-Nineties South African blues as performed by a bunch of White men unless it is meant to illustrate Sonny Boy Williamson’s famous observation on the British blues scene of the early Sixties: “these boys want to play the blues so badly and they play it so badly…”

It is a rock critic’s cliché to remark that a particular double album (this criticism originated in the vinyl LP era) would have been a better proposition if it had been reduced to a single disc. In the case of Sharp Street, the worthwhile tracks would make a decent EP.

One can contrast the 1970 Otis Waygood Blues Band album with Sharp Street, as an example of how excellent late Sixties style White blues can sound with committed playing and singing and sympathetic production. The Blues Broers would have been a totally different proposition if they’d had a proper vocalist, for example Howlin’ Mervyn Woolf who fronted The Flaming Firestones Mk I. Now, that is a band I’d like to hear on CD even if they too were not above indulging in blues rock bluster. Three vocalists! Two blistering harp players! A horn section! There must be some live tapes lying around in someone’s cupboard; maybe Rob Nagel has a selection, and with the current easy availability of the appropriate technology it should not be too difficult to create CD-Rs from such tapes. I guess one can but dream.

In the meantime we’ll have to be satisfied with The Blues Broers. Great name, though.

No comments:

Post a Comment